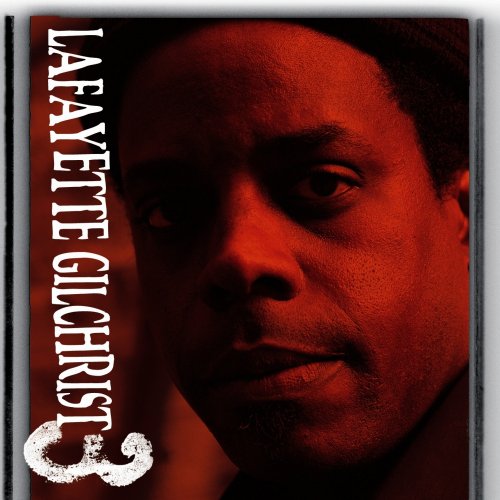

Lafayette Gilchrist - Three

Writer Geoffroy Himes is on a tear: along with the great article on Ryan Shaw, Robert Randolph and the pop vs. church conundrum for the NY Times I linked to yesterday, he's got an absolutely brilliant feature on Lafayette Gilchrist (myspace) in the Baltimore City Pages. There's also a companion blindfold test in which Gilchrist speaks freely on a wide array of musical and non-musical topics, a lot of which revolves around the music-society relationship.

The feature goes in-depth about Gilchrist's own style and branches out into a discussion of the challenges of melting contemporary beats into jazz.

one of the most vexing dilemmas in modern music: How can jazz transform the black popular music of today into complex improvisations as it once transformed swing and ragtime? Or, to turn the question around, how can funk and hip-hop shrug off their formalist straitjackets and stretch out into new musical territory?I first saw Gilchrist in David Murray's quartet maybe five or six years ago (with Jaribu Shahid and Hamid Drake). He impressed me by ably following anywhere the others went, from hard-driving groove to austere free improv. Afterwards, we talked a bit and he ended up singing Andrew Hill and Herbie Nichols lines to me.

(...)

These questions are vexing because the very quality that makes funk and hip-hop so pleasurable--the power and the precision of their beats--makes them difficult for jazz to digest. Jazz requires a rhythmic elasticity for the sudden shifts that make it so pleasurable. As thousands of bad fusion and smooth-jazz records have demonstrated, adhering too closely to a repetitive groove kills the pleasures of jazz. As thousands of straight-ahead jazz records have proved, abandoning the groove too often kills the pleasures of pop. How can you accommodate the best of both worlds?

I've been following his own work since The Music According To Lafayette Gilchrist, his first release on Hyena Records. On it and its follow-up, Towards The Shining Path, his band the New Volcanoes justified its name with heavy, dark funked-up jazz. The emphasis was on Gilchrist's fine horn voicings and arrangements and the solos of his sidemen, relegating the leader to intriguing comping and all-too-rare solos that stood out within a somewhat inflexible template. His third and latest is Three, on which he foregrounds his own playing by paring down to a trio and upping the quality of the compositions, notably that of the slower ones.

Gilchrist combines an old-school beat and fullness (see his comments on Eubie Blake, two-fisted piano and the relationship between music, dance and society in the blindfold test) with contemporary swagger and a dark, rumbling kind of harmonic daring. When he gets really worked up, the effect is great: you're dancing and thinking at the same time, as dense flurries, bluesy figures, melodic fragments and quiet, prolonged trills pirouette around sturdy syncopated beats.

While Jason Moran's trio weds loose, organic cycles of expansion and contraction to high-art concepts, Gilchrist's remains at street-level, producing its sparks in the tension between the short, syncopated riffs Anthony Jenkins and Nate Reynolds are tethered to and the great latitude granted the pianist to dive in and out of the groove. The thrill is in finding out what he'll do next, and Gilchrist's playing is strong enough to carry that burden.

|